Artemisia Gentileschi was born July 8, 1593, 431 years ago today. One of the greatest artists of the Baroque period, she is best known for using her paintbrush to create empowered female subjects, portraying them from a female perspective, in ways male artists rarely had. Rather than sitting passively, Artemisia’s women are active participants, strong, capable and defiant.

Artemisia Gentileschi was born July 8, 1593, 431 years ago today. One of the greatest artists of the Baroque period, she is best known for using her paintbrush to create empowered female subjects, portraying them from a female perspective, in ways male artists rarely had. Rather than sitting passively, Artemisia’s women are active participants, strong, capable and defiant.

Introduced to art and trained by her father Orazio Gentileschi, an early follower of the dramatic style of Caravaggio, Artemisia worked along with her 3 younger brothers. She was the only one to show talent and interest, producing her own work by age 15. In 1610, at age 17, she painted her earliest surviving work ‘Susanna and the Elders’ which for years was incorrectly attributed to Orazio. Unlike other painters’ versions, her Susanna is distraught and shields herself from the oglers, as an early depiction of sexual harassment. Artemisia painted this subject 7 times.

In 1611 Orazio decorated a palazzo in Rome with painter Agostino Tassi. He hired Tassi to tutor 17-year-old Artemisia to help refine her painting skills. During one of their sessions, he raped her. They started a relationship, since she believed they were going to be married, as societal norms of the time required. When it became apparent that Tassi was not going to marry Artemisia, Orazio took the unusual route of pressing charges against him for rape. The trial went on for 7 months, revealing scandalous details -that Tassi had an affair with his sister-in-law and allegedly hired bandits to murder his missing wife. Artemisia was subjected to a gynecological exam, and tortured with thumbscrews to verify the truthfulness of her testimony! Luckily there was no permanent damage to her fingers and this did not affect her ability to paint. Tassi was convicted, and sentenced to 2 years in prison. He was also exiled from Roma, but this was never enforced.

After this ordeal, many of Artemisia’s paintings feature women being attacked or in positions of power, seeking revenge. In 1612 she painted her first of 6 versions of Judith Slaying Holofernes, which is in Museo Capodimonte, Napoli. The 1620 version in the Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze is ‘bloodier’ than the first one. I like to imagine Artemisia having a scientific discussion with Galileo about realistic blood spatter patterns! Below is Caravaggio’s 1598-99 version of the scene, which is a masterpiece, but Judith looks like the 90 pound weakling who is worried about breaking a nail or getting blood on her dress, and her servant just stands there. In Artemisia’s version, both women mean business, practically sitting on Holofernes to get the job done.

After the trial, Orazio arranged for Artemisia to marry artist Pierantonio Stiattesi and they moved to his home city Firenze, where she had a successful career as an artist and an impressive clientele. She had the support of Cosimo II de Medici and was friends with Galileo.

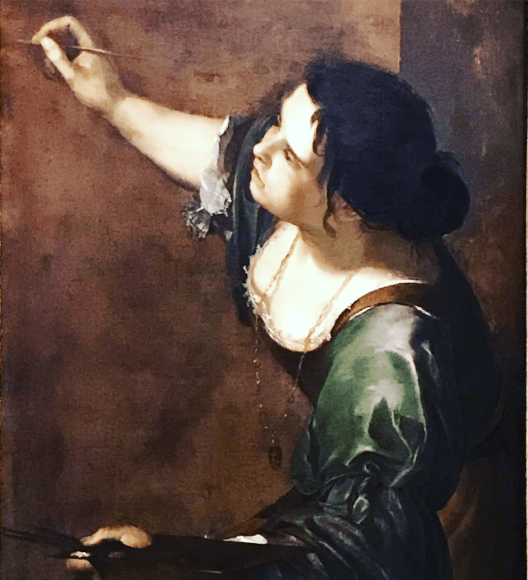

At age 21, Artemisia was the first woman accepted into the prestigious Firenze Accademia delle Arte del Disegno. This was a major accomplishment! She was now able to sign her own contracts and purchase art materials without permission from her husband! In 1615, she was commissioned to paint one of the ceiling frescoes at Casa Buonarroti, former home of Michelangelo, being turned into a museum by his great-nephew. Artemisia was paid more than the male artists working on the frescoes were! ‘Allegory of Inclination’, like many of her paintings, was likely a self-portrait. Why self-portraits? The model is free and always available!

In 1618 Artemisia had a daughter named Prudentia, the only one of her 5 children to survive infancy. She trained Prudentia as an artist, although none of her work survives that we know of. Artemisia had an affair with Florentine nobleman Francesco Maria di Niccolo Maringhi, which is documented in a series of 36 letters, discovered in 2011. Her husband also corresponded with Maringhi, who helped support them financially. Fed up with her husband’s financial and legal issues, she returned to Roma with her daughter in 1621-1626. Artemisia continued to be influenced by Caravaggio as she worked with some of his followers, Carravagisti, including Simon Vonet. She also spent 3 years in Venezia working on commissions.

Artemisia relocated to Napoli in 1630 and worked with many well-known artists such as Massimo Stanzione. In 1638, she was invited to the court of Charles I of England in London, where Orazio had been court painter for 12 years. He was the only Italian painter in London and the first to introduce the style of Caravaggio there. Orazio and Artemisia had not seen each other for 17 yrs. She worked alongside Orazio on an allegorical fresco for Greenwich, residence of the Queen. Orazio was 75 and needed her help to complete the work before he died suddenly in 1639. Artemisia painted some of her most famous works while in England, including Self Portrait as Allegory of Painting (1639), which she likely painted with 2 mirrors, one on either side of her. In 2017 I had the opportunity to see this painting at the Vancouver Art Gallery exhibit from the Royal Collection.

Once she finished her commissions, Artemisia left England before 1642, returning to Napoli. The last letter from her agent was dated 1650, which implies she was still painting. There is additional evidence to suggest she was still working in Napoli in 1654 and likely died during the plague in 1656.

Artemisia’s legacy is complex and full of controversy. She defied the odds and was well respected as an artist during her own lifetime. She thrived in a time when women had few opportunities to pursue artistic training, let alone actually work as professional artists. After her death, Artemisia Gentileschi was almost omitted from the history of art. The fact that her style was much like her father’s and some of her works were incorrectly attributed to Orazio and even Caravaggio may have something to do with that. More likely, those documenting art history did not think a woman was worth mentioning.

In the early 1900’s, her work was rediscovered and championed by Caravaggio scholar Roberto Longhi. In all accounts of her life, Artemisia’s talent and achievements are overshadowed by the story of her rape and trial. This is partly due to a 1947 over-sexualized fictional novel by Longhi’s wife Anna Banti. 1970’s and 80’s feminist art historians began to reassess Artemisia and her reputation, focusing on her significant artistic achievements and influence on the course of art history rather than events that happened in her life.

A 1976 exhibition ‘Women artists 1550-1950’ proposed that Artemisia was the first female in the history of Western art to make a significant and important contribution to the art of her time. Following centuries of near obscurity, today Artemisia’s paintings are again celebrated around the world. An ornate plate rests in her honour at the table of contemporary feminist art as part of Judy Chicago’s iconic 1979 work ‘The Dinner Party’.

Artemisia has left us with 60 paintings, not including collaborations with Orazio. 40 of them feature females from the Bible or mythology. Only 19 of her paintings are signed and 13 are in Private collections! Can you imagine owning your own Artemisia??? Famous quotes from Artemisia include ‘My illustrious lordship, I’ll show you what a female can do’ and ‘As long as I live, I will have control of my being’.

Enjoy the Monologue ‘Becoming Artemisia'(May 2024) directed by Antonio D’Alfonso, text by Mary Melfi (17 min).

Photo credits: Susanna and the Elders and Allegory of Inclination, Wikipedia

Google Doodle by Hélène Leroux, July 8, 2020

All other photos taken by Cristina